History

The first European pioneers to settle the area which would eventually become the village of Lantz Mills arrived in the 1750s. The site became a prosperous mill village and a center of industry and commerce by the mid-19th century, with a post office, forge, harness shop, gristmill, sawmill, and cider mill, and a tannery in operation. In the late 19th century, there was an important mercantile store operated by Jacob Clem, as well as a carpentry, woodworking, and casket making shop owned by William Christian. Rifles marked “Kauffman” are known to have been made in the area, as were wooden washing machines1. John B. Milligan operated a general store; George Rinehart ran a dry goods store; and Fadley Harrison and James Foltz operated a distillery.

The Lantz Mill today sits on a lot of slightly more than an acre in the center of the village. The mill property, however, started out as a much larger property. The first in the chain of deeds recorded in the Shenandoah County courthouse pertaining to the property is a land grant from the proprietors’ office of the Northern Neck of Virginia, dated October 8, 1766, which granted 372 acres to Peter Hollow (Holler).2 Lord Fairfax, however, forfeited Holler’s grant and on November 21, 1770, gave 340 acres to Christopher Cofman.3 In 1790, Holler purchased 200 acres back from Cofman.4

will and testament, after his death in 1813. The 1814 appraisement of Peter Holler’s estate indicates that John Holler inherited 100 acres, the gristmill and the residence, and Henry Holler inherited the sawmill. This is the oldest document found thus far to specifically mention the gristmill, which would subsequently become known as the Lantz Mill.5 It is logical to assume that the mill predates the date of Peter Holler’s will, but no documentary evidence has yet been discovered which would establish the original date of construction. The 1810-1816 Shenandoah County Minute Book records a decision by the Justices to task Peter Holler with opening a road “leading from Columbia Furnace on Stony Creek, passing the Union Forge” then joining the road from Woodstock to Staunton (modern day Route 11)6. Holler presumably had an interest in the construction of such a road, either because his mill already existed or would soon exist, and the road would have facilitated the export of his flour to Edinburg, then to Luray, Virginia, then down the South Fork of the Shenandoah River and the Potomac to the important international flour market located in Alexandria, Virginia. Most of the agricultural products arriving at the Alexandria market came from the areas now comprising the 15 northern Virginia counties, a region that had been the principal wheat producing area of Virginia since the Revolutionary War.7

On September 7, 1815, the Holler brothers sold the mill property to Samuel Morrison Burnside Stuart8, who in turn sold the mill to George Adam Lantz (1788-1869) on January 1, 1824;9 The mill would remain in the Lantz family for the next 72 years. George Adam Lantz was the grandson of one of the pioneers of the hamlet of Lantz Mills, Hans George Lantz (1725-1793), who came to America from Germany in 1747 and settled along the Monocacy River in Maryland. In 1766, Hans George Lantz moved to Shenandoah County, Virginia, where, under the name of George Long, he received a grant from Lord Fairfax of 470 acres of land on Swan Pond Hollow, “a drain of and on the south side of Stony Creek”.10 Both he and his son, Jacob Lantz (1759-1837), supported the revolution against Great Britain, contributing wheat, bacon, and beef to the Continental Army.11 Jacob Lantz later became a long-serving magistrate of Shenandoah County.12

In January 1833, George Coffelt (Coffield), a neighbor, sold George Lantz the rights to maintain a dam and a race which ran through his land to power Lantz’s mill13. Coffelt owned two large tracts of land along Stony Creek–the first was granted in 1766 and consisted of 300 acres on both sides of the creek and the second, consisting of 400 acres, was located on the “North Westerly Side of Stony Creek”, and was obtained in 1774.14 From the wording of the 1833 easement it is clear that George Lantz’s mill pre-existed the sale of these rights. It is likely that part of the mill-race and the dam had been built when the land on both sides of Stony Creek was owned by Peter Holler. When Lantz bought the mill tract on the north side of Stony Creek, he may have done so forgetting to retain easement rights on the south bank of the creek, or he may have encroached, inadvertently or not, on his neighbor’s land.

In 1863, Jacob Lantz (Jr.) (1814-1883), purchased the mill tract from his father George, which at this point in time consisted of 102 acres15 and which was known as the “mill tract”16. It is clear, however, that Jacob had been running his father’s business at Lantz Mills for many years prior to actually becoming the owner of the mill tract, given especially that George Lantz was 75 years old at the time of sale. It was Jacob Lantz, not his father, who was listed in the Thompson’s Mercantile and Professional Directory for Virginia in 1851 under the category “General Dealers in Dry Goods, Groceries, Hardware, &c.” doing business at Lantz Mills.17 Jacob Lantz was also a partner in the Edinburg Manufacturing Company, chartered May 1, 1852, to produce woolen goods, flour, and lumber. George Grandstaff (the owner of the Edinburg Mill), Jacob Lantz (Jr.), Cyrus Springer, Peter Celow, and John J. Allen held the company’s capital stock, which was not less than $10,000 nor more than $100,000 each in shares of $25.18 Presumably the lumber and flour from Lantz’s mills were marketed by the company.

By mid-century, Jacob Lantz had become the principal merchant for Lantz Mills, “dealing in all kinds of articles”. His large mills “supplied the flour and grain for a large trade. His sawmill and shops turned out various products”. At the beginning of the Civil War, he was one of the chief businessmen of the area and was a staunch supporter of the Confederate States of America. Jacob was the presiding Justice of the Peace for Shenandoah County, and all of the fractional currency issued by Shenandoah County during the Civil War bore his signature.

Whenever Union troops arrived in the area, Lantz was forced to go into hiding.19 In October 1864, Union Major General Wesley Merritt, in command of the First Cavalry Division, laid waste to farms and industry along the Middle Road and the Valley Pike in Shenandoah County. Noted local historian, John L. Heatwole, wrote in his book, The Burning, that “by late afternoon [on October 7] cavalrymen of the Second and reserve brigades approached Stony Creek … behind them the countryside was filled with smoke, and the wind carried the strong smell of wet ashes. At the bustling and lovely hamlet of Lantz Mill, two miles west of Edinburg, they continued their acts of arson”.20

Jacob’s eldest son, Jacob Wissler Lantz, would later describe the reason for his father’s ordeal and the events of the evening of October 7, 1864, which included the burning of the gristmill:

He was a Justice, the highest elective office I ever know a Lantz to hold, and this probably paid him $5.00 or $10.00 a year but it was a great pleasure to him. In his day and time I think the Justices of the county met and elected one to try the important cases, probably appealed from the regular justices, and to this he was elected or appointed. This office corresponded to our county judges and had more honor or at least more responsibility. I remember it cost him his home and nearly all his property. Some Northern soldiers had been captured by the Southern Army and in passing through the county, the Southern soldiers were overpowered by a mob and [a] Northern soldier [was] killed. [Later] orders were issued [by a] Northern officer to arrest father for he was the trial justice, [and also to arrest] Colonel Rinker who commanded the soldiers that allowed the mob [to kill the Northern soldier]. They were also ordered to burn their dwellings. They burned father’s house, but not until they gave his slaves ten minutes’ time to carry out the household goods, and after these things had been carried out they also burned them. Some Southern officer sent a flag of truce, and a note that for every house burned they would kill ten Northern prisoners. This note was too late for my father’s house but did save Colonel Rinker’s. Later they arrested father but released him for some cause I do not think he ever knew.21

As the presiding Justice of the Peace, Jacob Lantz was sought out by Union troops for failing to arrest his neighbors for their guerrilla warfare. He was targeted during the Burning and as a result all his buildings were destroyed including his “dwelling house, store houses, shops and flour mill.”22 The Union force burned much of the village of Lantz Mills and permanently destroyed the nearby Union Forge, owned and operated by Jacob’s half brother Samuel Lantz23. As a result of the ”The Burning”, the appraised value of the buildings, including the mill, located on the Mill Tract, plunged to zero in 1866 from $3,600 before the war.24

The mill was rebuilt around 1867 on the limestone foundation of the antebellum mill. The stones today still display much evidence of sprawling due to the extreme heat from the fire; a small portion of the original foundation was rebuilt as well. The mill was rebuilt as a stone grinding operation 25, or “New Process” mill, as roller mill technology was not introduced into the United States until 1876 and was not widely available in country mills until the late 1880s26. Grinding stones, dating from the pre-Civil War mill, were known by local residents to have been lying around the mill property until the mid-1980s, when they were “liberated” by relic hunters.27

The reconstruction date is obtained through the Shenandoah County tax book of 1867, which shows a value of $2,550 for the “New Mill”.28 The reconstructed mill contributed to the economic recovery of the village of Lantz mills and surrounding farming operations. Only two mills along Stony Creek had survived “The Burning”–the Edinburg Mill and the Whissen Mill, also located at Edinburg.

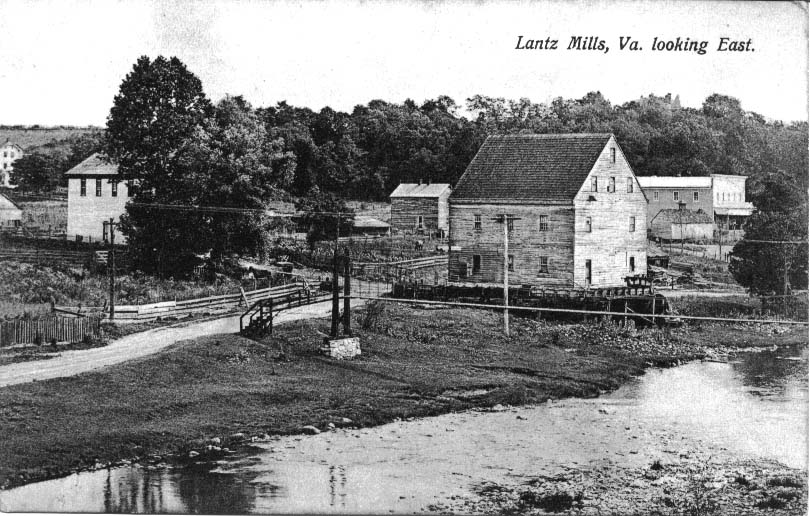

The Lantz Mill was one of the first local mills to be reconstructed after the war, playing an important role in the area’s commercial and industrial recovery. The 1870 US Census of Industry for Shenandoah County listed Jacob Lantz’s mill as being a 30-horsepower water-driven mill operating with two burr-stone grinders. The mill was appraised at $7,500. The census also indicates that in 1870, Lantz paid $500 in wages to his miller, and that the mill produced 1,600 barrels of flour, worth $10,000; 112,000 pounds of rye chop, worth $1,200; and 112,000 pounds of corn meal, also worth $1,200.29 The 1880 census shows that the mill produced 1000 barrels of flour, 2000 pounds of buck-wheat, 320,390 pounds of corn meal, 82,000 pounds of “feed”, 1200 pounds of hominy for a total production value of $10,00030. The slight drop of in production from 1870 to 1880 was probably due to an increase in milling competition, as by 1880, the mills that were burned during the Civil War would have been rebuilt, and other new mills would also have been constructed. Interestingly, the 1880 census indicates that the mill had two overshot waterwheels. One of the wheels was likely used to power the flour mill, and the other was probably used to power Lantz’s sawmill. The sawmill was recorded separately from the flour mill in the 1880 census, but because the characteristics of the height of the fall of the water and the horsepower of the waterwheel are identical to those recorded for the flour mill, it is probable that the sawmill and the flour mill were both housed in the same mill building. The 1885 Atlas of Shenandoah and Page Counties indicates that the flour mill and sawmill were the same operation.31 A circa 1895-1898 photograph shows what was likely the sawmill portion of the complex32. Interestingly, this portion of the mill had been removed by the time postcard of the mill was produced in 1908.

In 1879, Hite Byrd and M. L. Walton were appointed by the Shenandoah County Court to liquidate Jacob Lantz’s assets after he became bankrupt. He was never able to overcome the losses he suffered as a result of the Civil War. The Commissioners sold the mill tract which contained “the houses, flouring and saw mills and tannery”33 and consisted of 103 acres, to Jacob’s second wife, Elizabeth H. Lantz, widow of Confederate Major Samuel Meyers, for $7,046.99.34 Mrs. Lantz had earlier obtained the money for the purchase from her father, Christian Whissler.35 Through his wife’s ownership, Jacob Lantz was able to continue his businesses and keep his residence until his death four years later.

On January 10, 1895 Elizabeth Lantz conveyed “the merchants mill, saw mill, store house, dwelling house and outbuildings” and 20 acres to Joseph B. Tisinger for $7000”.36 Joseph Tisinger, in turn, sold the mill to Erasmus T. Smith for $2,300 on April 1, 1898. The final acreage and meets and bounds for the lot upon which the mill sits today are defined through this deed.37 It is likely that Tisinger updated the milling equipment in the building with the most modern roller mill technology at or about the time of purchase, as most of the extant equipment dates from the late 1890s, and represents the pinnacle of roller mill technology before the mass industrial production of flour. From 1930 to 1959, William I. Wilkins operated the mill as “Lantz Roller Mills”.

On August 22, 1959, William I. Wilkins went into bankruptcy and the mill was sold to Roscoe H. Sine, Ira C. Sine, Clen N. Sine, Eldred D. Sine, and Berlin G. Sine, Partners, trading under the name “Sine Brothers” for $1,375;38 The Sine Brothers operated the mill as a feed mill, as industrially-produced flour was readily available by then in stores. The Sine Brothers dealt exclusively in grain, feed, and medicines for animals.39 Two of the animal feed products produced were a “Shenandoah Breeder Mash” and the “Sine Hog Finisher”. The first was a mix of corn meal, wheat bran, wheat middlings, pulverized oats, dehydrated alfalfa meal, meat scrap, soybean oil meal, ground barley, wheat germ oil, vitamins A and D, feeding oil, salt, and pulverized limestone. The “Finisher” was a similar mix of ingredients with more vitamins and Red Rose Hog Supplement. The Sine Brothers closed their business in 1980.

-

Williamson, May Anne, and Davis, Jean Allen, The History of Edinbug, Virginia, CommercialPress Inc., Stephens City, Virginia, 1994, p. 21. ↩

-

Northern Neck Grants N, 1766, p. 268 (Reel 295), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. Granted under the name Peter “Hollow”. ↩

-

Northern Neck Grants O, op. cit., 1767-1770, reel 296,.p. 335. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book H, p. 222., Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Will Book I, p. 84, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Court session of November 13, 1810; Shenandoah County Court Minute Book, 1810-1816., Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Peterson, Arthur, G., “The Alexandria Market Prior to the Civil War”, William and Mary Quarterly, 2nd Ser., Vol. 12, No. 2 (Apr., 1932), pp 107-108. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book W, p. 68, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book DD, p. 68, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Lantz, Jacob Wissler, The Lantz Family Record, Cear Springs, Va., 1931, p. 49. See Also Northern Neck Land Grants, N, 1766, reel 295, p. 264, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. recorded under the surname “Long”. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Court Minute Book, 1781-1785, May 31, 1782, p. 54 Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va; and, Public Service Claims, Commissioner’s Book, V, November 27, 1783, p. 158, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Court Minute Book, 1806-1810, and 1810-1816, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Virginia. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book OO, p. 28, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Northern Neck Grants, P, 1771-1775, p. 120 and 261, respectively, reel 296, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book 7, p. 209, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Ibid, p. 53 and 222. ↩

-

Thompson’s Mercantile and Professional Directory, Virginia, Shenandoah County, 1851. ↩

-

Wayland, John W., A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia, Shenando7ah Publishing House, Strasburg, Va., 1927, p. 292 ↩

-

Heatwole, John L., The Burning, Howell Press, Inc., Charlottesville, Virginia, 1998, p.180 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., p IV-V ↩

-

Ibid., p. 222. ↩

-

Ibid., p 181. ↩

-

1859 and 1866 Shenandoah County Tax Book, Nathan Barton District, page 30, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

The 1870 Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Shenandoah County, Virginia shows that the mill used two burh stone grinding machines; see the 1870 Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Virginia 1850-1880, 1870 Industry Schedule, Publication Number T1132, microfilm roll 15, National Archives, Washington D.C. ↩

-

Dedrick, op. cit., pp.97-98. ↩

-

Conversation with Jennifer Bender-Moran a previous owner of the mill, based on her conversations with Anne Cottrell Free, deceased, a long-time resident of Lantz Mills. ↩

-

1867 Shenandoah County Tax Book, op. cit., p. 30. ↩

-

Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Virginia, 1850-1880, 1870 Industry Schedule, Publication Number T1132, microfilm roll 15, National Archives, Washington D.C. ↩

-

Nonpopulation Census Schedules for Virginia, 1850-1880, 1880 Industry Schedule, Publication Number T1132, microfilm roll 32, National Archives, Washington D.C. ↩

-

Lake, J.D. & Co., Atlas of Shenandoah and Page Counties, Virginia, 1885, reprinted by G.P. Hammond Publishing Co., Strasburg, Va., 1991, Madison Magisterial District. ↩

-

The exact date of the photograph is uncertain. One can surmise it was taken between 1895 and 1898, as the house located on the far left of the photograph (today occupied by Mr. Earl Didawick Jr.) was constructed in 1895, and the Lantz Mills footbridge, constructed in 1898, is not visible in the photo. ↩

-

The two houses in question still exist and are the house Lantz rebuilt at the same time he rebuilt the mill in 1866 and which is a grand Victorian house located across Swover Creek Road from the Mill in which his widow lived until 1903, and an imposing brick colonial also across the road, built by George Lantz in 1842. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book 28, p. 21, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Lantz, Jacob Wissler, The Lantz Family Record, Cedar Springs, Va., 1931, p. IV. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book 45, p. 316, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book 48, p. 350, Shenandoah County Court House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Shenandoah County Deed Book 200, pp. 379-380, Shenandoah County Cou rt House, Woodstock, Va. ↩

-

Stoneburner, Paul, e-mail to Christopher Hernandez-Roy, April 2, 2005. ↩